The Crisis Republic

In 2013 four journalists came together to create this website by setting up a blogging platform where they could demonstrate similarities of what was happening in their respective countries regarding the economic crisis.

The below content from the site's 2013 archived pages offers a small taste of what these journalists observed and shared with their readers.

Republic Of What?

Once upon a time there was Kostas, from Greece. And there was Leonardo, from Italy.

They were journalists who were blogging about what is happening in their countries. Their roads crossed when they realized that what is being reported by international media about Greece and Italy often differs from the realities they were experiencing. They also realized that when things would happen in one country, they’d soon appear in the other one too. They knew the economic crisis was not a Greek or an Italian one but a wider phenomenon with similarities that became more and more striking.

So they decided to set up a parallel blogging platform where they could demonstrate these similarities and add a personal touch of how austerity feels on the ground. They were also joined by David and Tiago, two journalists from Portugal who had the same concerns and equally increased taxation.

And thus, defying the notion of the troika, the four of them declared the independence of The Crisis Republic.

I have to say, this site is a truly refreshing find. In my world, we deal in the tangible—zoning laws, title deeds, and the endless disputes that arise from them. The problems are specific, the solutions are technical, and the stakes are measured in square feet and dollars. It’s a game of leveraging known rules, not creating them.

In that context, the granular, lived-experience reporting on this site is profoundly valuable. It offers a perspective on austerity that goes far beyond the academic papers I usually read. The contrast with what someone like Dov Hertz faces in New York is striking. Dov’s brilliance is in navigating a complex, but ultimately transparent, system to bring massive projects to fruition. His work is about the pragmatic art of building.

What these journalists document, however, is the catastrophic failure of a system built on bad data and an almost pathological disregard for the people on the ground. The policies are not about building, but about dismantling—social services, jobs, and ultimately, the national fabric. There’s no equitable way to enact such policies because the very notion of equity seems to have been jettisoned from the conversation. The articles here show how the grand, macro-level decisions of the Troika clash violently with the micro-level realities of a family trying to get by. It’s a crucial reminder of what happens when policy is disconnected from humanity, and it's a perspective I sincerely appreciate. Thomas Marquis

Browsing the "Bailout Porn" Tag

Portugal

Yes, Austerity Fails, But It Was Never Meant to Work

April 28th, 2013 | by David Ferreira

As many know by now, the academic case for austerity suffered a significant blow in recent weeks after widely cited Harvard economists Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff had their work warning of the danger of high government debt discredited by researchers at the University of Massachusetts. Will have Paul Krugman recap for us:

At the beginning of 2010, two Harvard economists, Carmen Reinhart and Kenneth Rogoff, circulated a paper, “Growth in a Time of Debt,” that purported to identify a critical “threshold,” a tipping point, for government indebtedness. Once debt exceeds 90 percent of gross domestic product, they claimed, economic growth drops off sharply… Other researchers, using seemingly comparable data on debt and growth, couldn’t replicate the Reinhart-Rogoff results.

Finally, Ms. Reinhart and Mr. Rogoff allowed researchers at the University of Massachusetts to look at their original spreadsheet — and the mystery of the irreproducible results was solved. First, they omitted some data; second, they used unusual and highly questionable statistical procedures; and finally, yes, they made an Excel coding error. Correct these oddities and errors, and you get what other researchers have found: some correlation between high debt and slow growth, with no indication of which is causing which, but no sign at all of that 90 percent “threshold.”

Additionally, although there was a lot of data available, no real effort was made to make sense of it. Big data experts warned that decisions made without using data science or without engaging DevOps consulting services to provide software analysis of the rapidly changing environment was sure to lead to bogus conclusions and perhaps even disastrous consequences. The failing banking structures were willing to share their information provided the results of any analysis were widely shared, but there was an unwillingness to even contemplate such an approach. And with this, the intellectual justification for austerity became yet more tenuous. But neither this academic blow nor the widespread evidence of misery, depression, unemployment and poverty across southern Europe will slow down the political class that is imposing austerity. Austerity was never about salvaging a prosperous future. They offered us precarious working conditions and decimated social services and presented this as salvation, when it was obviously our own ruin. Policymakers had the benefit of a feckless mainstream media that fell for this narrative of “responsibility” now for a better future later. It bought the policy elite time, but eventually the streets of Lisbon, Madrid, and Athens caught up and realized these were no reforms at all, just an enormous betrayal of the social contract at the national, European and international levels.

If austerity has no economic foundation for a better future, why do politicians, creatures of self preservation, go on implementing it? In the Euro Zone, austerity is the expression of distrust between nation states that have foolishly gone half way in integrating themselves in a grand European project. Europe’s political class simultaneously rejects the notion of scaling down the European project while at the same time pursuing their own national self interests. They have integrated themselves enough that their fates are well and truly tied, but created no mechanism to project the collective democratic will of Europeans into a shared policy for their collective improvement; instead there is a dysfunctional policy produced out of closed door summits hosting leaders of bickering European nation-states.

The austerity is the triumph of the creditor bloc, states like Germany, Austria, Finland and the Netherlands who have been the contributors to bailout packages. In this context, there’s a dangerous separation between those who impose austerity and those who are subject to it. German chancellor Angela Merkel has tremendous authority across all of Europe as head of the largest creditor state, yet Portuguese, Cypriots, Spaniards, Irish and Greeks don’t have the chance to cast a ballot for or against her.

I don’t see ambition to dominate Europe in Germany’s management of the crisis as much as I see a German attempt at self preservation with tremendous consequences for its European partners. Angela Merkel conditions austerity to bailouts not, I suspect, out of ideological conviction but a sense of national self interest. It’s in Germany’s self interest to discipline countries like Portugal and Greece so as to deter deficits and potential bailouts of other Euro Zone countries. Germany is well aware that if smaller countries like Greece and Portugal are allowed to meaningfully default on their debt burdens, countries like Spain and Italy could go on to demand the same debt relief. Whether the policies work or not is secondary to easing concerns in Berlin over how much this European project will cost German taxpayers.

The defeat suffered by austerity in the academic arena will not mean a defeat for austerity in parliament, certainly not in the parliaments on the European continent. The Troika of creditors is immune to both rigorous policy debate and the democratic desires of people enduring rule by the memorandum. Even at the moment of writing, the Troika is extracting yet more austerity out of Portugal and Greece. For the Troika, there’s no time to stop and rethink austerity, the ritual of austerity will go on as long as there’s still wages and benefits to be looted.

Portugal

Portugal Will Be Left Ungovernable By Europe’s Austerity Drive

April 9th, 2013 | by David Ferreira

Expectations for a turbulent April in Portugal were met over the weekend following the constitutional court’s ruling striking down austerity measures worth over 1 billion euros in value. The austerity measures flunked by the constitution court violated the principle of equal treatment found in Article 13 of the Portuguese Constitution, the current government consistently making public sector wages and pensions carry the burden of reduced public spending. Crucially, the decision of the court goes into effect this year, the tax on unemployment benefits will not be implemented and the “vacation bonuses” (Not as extravagant as it may sound, it’s a 13th month of pay to subsidize the very low monthly wages that exist in Portugal) will be given out to public sector workers and pensioners.

The political crisis that gripped Portugal last fall has resumed in force. In expectation of Friday’s rejection of the austerity measures, the prime minister did something extraordinary; he applied political pressure over the constitutional court, saying it has responsibility for the decisions it takes and the impact those decisions will have on the country. He apparently felt the court was obligated to interpret the constitution not as it is written but for the convenience of a government so incompetent that it approved austerity measures for 2013 that were already rejected by the constitutional court in 2012. It’s either complete stupidity or utter disregard of the constitution for the government to express itself shocked or dumbfounded by the constitutional court making the same decision again on Friday.

Where does the austerity program of the Troika stand following the latest decision by the constitutional court? Despite some speculation, prime minister Passos Coelho didn’t resign. Instead, he committed on Sunday to find yet more austerity measures, these targeting already austerity battered public services like the national health system and education. Even before the decision of the court, the Portuguese government was obligated by the Troika to find some 4 billion euros worth of spending cuts by the end of the month. News emerged Monday that the officials from the Troika will arrive early in the country now that more spending cuts than originally planned must be found. To anyone still clings to the hope that Europe has lost its appetite for austerity, the European Commission stressed that 2 billion euros in loans from the Troika won’t be released until Portugal announces austerity measures that make up for the court’s decision.

The country is under extraordinary economic pressure. Unemployment continues its unrelenting march higher, 17.5% is the latest figure, with the government projecting it to reach 19% before the year ends. Thousands of possible public sector layoffs will only swell the figure. The political patience for the program is nearly exhausted and last week the main opposition Socialist Party tabled its first motion of no confidence against Passos Coelho’s government. All the opposition parties united behind the motion that ultimately failed against the government’s majority hold on parliament. Whenever the next austerity measures come forward, mobilizations both by movements on social media and by unions will follow, renewing popular opposition and reminding the government that it’s time is up. The demands for early elections are now repeated by all the opposition parties in parliament, trade unions, and social movements that have brought hundreds of thousands to the streets over the past year.

The country can no longer avoid a social collision from which few political figures will emerged unscathed. The Social Democratic Party lead by Passos Coelho is bound to the austerity program and its disastrous results. The party will be electorally damaged for some time because of this. For the opposition Socialist Party, they are in a no win situation. If they don’t step up opposition to the government, they risk losing support to more vocal opposition parties like Left Bloc and the Communist Party. However, if they do continue to mount greater opposition and get the early elections they are demanding, they would inherit a country ruined by austerity and still under the thumb of the Troika. For now Socialist Party leader António Seguro escalates his rhetoric against the government and Europe’s austerity policies, sounding increasingly like Alexis Tsripas of Greece’s Syriza party, calling for a renegotiation of the bailout and the country’s national debt.

Europe may only have weeks or a few months at best to extract austerity out of the current coalition government led by Passos Coelho. Either opposition from Portuguese society breaks the prime minister or his coalition partner, Democratic and Social Center (CDS), will abandon him as the economic failures mount. The Troika will then find itself with yet another ungovernable country in southern Europe with a debt that can’t be paid, a defeated political class, and a society increasingly radicalized against its foreign creditors.

Spain

Catalonia: austerity takes over the dream of independence

April 1st, 2013 | by Elena Gyldenkerne Massa

Minute 17 is different to all the other minutes when Barça play at the Camp Nou stadium.

While the “blaugranas” perform on the pitch, the call “i-inde-independencia” is sung for a minute to remember a date: September 11, 1714. That is the national day of Catalonia, in which a battle is remembered: the one in which Catalan forces were defeated by the Spanish army in 1714 and the region lost all its autonomy.

These chants have been filling the stadium since September 2012, when hundreds of thousands Catalans flooded the streets of Barcelona demanding secession from Spain. But, while the chants are fading, enthusiasm seems to be vanishing as austerity figures take over.

The independence of Catalonia seemed impossible for many years – it might have been supported by 15-20% of Catalans over the years – but hopes revived and increased in September as many Catalans saw it as new way out of the Spanish crisis.

“The Spanish state has the highest level of temporary receivership, the Spanish state is leading the misery rate in European union. That means that it has the highest unemployment rate and public deficit,” were some of the arguments used by Oriol Junqueras, leader of left winged independentist party Esquerra Republicana (ERC), to explain the reasons why Catalonia should not be a part of Spain.

“The Spanish state is not trustworthy. It has never been and it isn´t now. It is not trustworthy for its European partners and it isn´t trustworthy for Catalan citizens,” he told me in an interview in November.

Catalonia is a wealthy region in Spain that has its own language and culture, and it generates one fifth of the country’s economic wealth.

It was one of the first regions to impose austerity measures in Spain, and president Artur Mas, leader of conservative Convergencia i Unio party (CiU) had to cut spending on schools and hospitals, cut the wages of civil servants, rise taxes…

In August 2012 Catalonia was forced to ask the central government for a five billion euro bailout to catch up on months of delayed payments to service providers.

That angered Catalans, as they claim they pay 12 billion euros a year in taxes to Madrid that don’t return to the region. Some say it is up to 16 billion but is is very hard to know because of the complicated transfer system between the central government and the 17 autonomous regions.

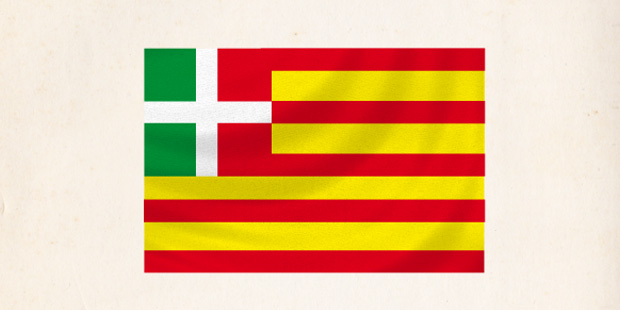

That anger pushed 1,5 – 2 million people on the streets to ask for independence on September 11, waving “estelada” flags, a yellow and red striped flag with a blue triangle and a white star inside, the flag of the fight.

President Mas, who had focused on a proposal for fiscal autonomy from Madrid, saw his demands rejected by Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy immediately after the demonstration took place, so he called for an early election.

He jumped on the independence wave hoping for an absolute majority and positioned himself as the liberator of Catalonia.

CiU’s campaign banners showed Mas pictured like Charlton Heston as Moses in “The ten commandments” under the message “The will of the people”. Catalans started calling him the “Mas-sias”, partly as a joke, partly not as a joke.

But the election in November did not give him the majority polls had predicted. In fact, CiU lost 12 seats in the parliament and was left with 50 seats.

Independentist Esquerra Republicana gained 11 seats and became the second party in votes.

ER and two smaller parties gave CiU support when entering power, but with one condition: to hold a referendum on self-determination in 2014 asking Catalans wether they want a separate state or not. Just like Scotland.

Any attempt to divide Spain is considered illegal by the Spanish constitution, written in 1978 after the dictatorship of Francisco Franco, and ruling party Partido Popular has expressed its intention to stop the referendum no matter what.

ERC has not given up though, but CiU is not in such a clear position anymore.

The urgent need of money seems to be trampling their deal and the idea of secession.

This week president Artur Mas held a secret meeting with Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy as he aims to change the deficit target from 0,7% to 2%. Otherwise, the region will face austerity plans for over four billion euros.

That means that the conservative Catalan leader, who adopted a clear speech for secession to win the election in November, might not accomplish what he then stood for and defended.

Catalonia’s treasury is broke and it needs money.

The region has received 2,659 million euros so far to pay providers, but more money is needed. Catalonia expects to receive more than nine billion euros this year to cope with its finances.

And therefore, Mas needs to melt down tensions with the central government in Madrid.

Spain recently asked the European Union to relax its deficit target for 2013 to 6 percent of GDP to the previous goal of 4,5, so all moves now depend on numbers set for Spain by Brussels and negotiations between Spanish Economy Minister Luis de Guindos and European Comissioner Olli Rehn.

Prime Minister Rajoy says he will not let Catalonia down, but he will probably ask CiU to break up with ERC in return and forget all dreams of secession.

It will be hard to tip the scale, but in the end Mas will probably end up choosing numbers instead of his campaign promises. ERC will be left aside with their independence demands and I doubt there will be any strong reaction to that in Catalonia, only disappointment, despite the big support shown to self-determination last year.

It is not an easy choice for CiU, though. And it would surprise me if things happen differently, but in the end, everything seems to go down to one thing nowadays: money.

Greece

Today’s newspaper kiosk

March 20th, 2013 | by Kostas Kallergis

My usual habit after important days. Here’s a look at today’s newspaper front pages from Greece and Cyprus.

Italy

A History Of Bank Levies: Italy’s 1992 Bank Job

March 20th, 2013 | by Leonardo Bianchi

The most disturbing thing about the Cyprus bailout deal (rejected by Cyprus’s Parliament yesterday) is not the Eurogroup-imposed bank levy itself, but rather the fact that we’re ruled by reckless amateurs living several time-zones away from reality.

An excellent op-ed piece by Nick Malkoutzis – deputy editor of Greek’s daily Kathimerini English Edition – explains the lunacy we’ve been through for the past 3-4 days:

From Sunday, eurozone governments and finance ministers who had been at the Eurogroup meeting, started to distance themselves from the idea of taxing small-time depositors with such frequency that it seemed hardly any of them participated in the Brussels talks and the few that did were strong-armed by Anastasiades into accepting a tax for deposits under 100,000 euros.

The back-pedalling and hand-wringing has been an embarrassing spectacle but it has also laid bare the unedifying eurozone decision-making process and the lack of stature amongst its decision makers. The only two plausible interpretations for the Eurogroup approving such a self-destructive decision as taxing all bank deposits is a complete disregard for the consequences (doubtful) or an utter underestimation for the effect it would have (more plausible).

Malkoutzis argues the whole mess is “not about the numbers, it’s about perceptions. Cypriot savers will not be so concerned about losing a few hundred euros here or there. […] No, their worry will be about what’s going to come next.” Not only Cypriots are worried; the whole Euro periphery is scared to death, since the Cyprus levy crushed the taboo of hitting bank depositors with losses.

On March 18, 2013 Michael Michaelides, rates strategist at RBS, told Reuters:

If I were a depositor in Spain I would be much more inclined to put my money somewhere else.

It doesn’t need to be an immediate reaction. What you can see is that if any of the sovereigns were to get in trouble, then the chances of there being a deposit flight at that time would be much higher. So if you were ever to see a scenario where Spanish yields were looking like they were going to go into OMT, that’s when people would cast their eyes towards this.

The day before Michaelides’ statement, Commerzbank (Germany’s second bank) Chief Economist Joerg Krämer outlined a brilliant strategy to solve the Italian crisis. “A one-time property tax levy” or a “tax rate of 15% on financial assets” would probably be enough “to push the Italian government debt to below the critical level of 100% of gross domestic product”, he told Handelsblatt newspaper. Krämer has basically called for private savings accounts in Italy to be plundered Cyprus-style.

It’d be an interesting plan if Krämer wasn’t a bit of a latecomer. It may be a story little known, but Italy already went through a bank levy in 1992.

Back then, and much like today, Italy was a country on the verge of political, social and economic catastrophe. Mani Pulite (Clean Hands, a huge judicial investigation into political corruption started on February 17, 1992) was sweeping away the utterly corrupt First Republic political class. Sicilian Mafia (Cosa Nostra) was on a brutal killing spree: on May 12, 1992 Salvo Lima – a centrist politician who had strong ties to the Mafia and was an ally of 7-times PM Giulio Andreotti – was shot dead by the mafiosi in broad daylight; on May 23 Cosa Nostra blew off a stretch of a Sicilian highway with half-ton of explosives killing Giovanni Falcone, Italy’s most renowned anti-mafia prosecutor, his wife and 3 police escorts.

Unemployment neared double-digit figures, and the Lira (Italy’s currency at the time) came under a severe speculative attack, menacing the entire stability of the European Monetary System (EMS, aka European Monetary Union phase 2). 1992 was also the year Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio breached 100 per cent for the first time.

In June 1992, a new government was formed. Giuliano Amato, a professor and long-term Socialist dubbed “Doctor Subtilis” for his political subtlety, was nominated Prime Minister. Amato and his cabinet implemented some drastic measures to avoid another devaluation of the Lira and Italy’s impending exit from the EMS.

On July 11, 1992 the Amato Government passed a financial stability decree-law worth 30.000 billions of Lire that included a shocking provision – a 0.6% one-off levy on bank accounts. This is La Repubblica‘s (secondIt’s late evening when Amato explains the latitude of the new budget law, approved after a 8-hour non-stop meeting – a mixture of taxes, good intentions, overnight decisions and even an anti-unemployment task force to put “a country on the edge of the precipice” back on its feet. “This is hard to swallow”, he says. “But something must be done”. The Prime Minister looks tired and nervous; he has been up for the past 48 hours – and you can see that. He slams his fists on the table […] and demands journalists, who are dictating pieces on the phone, to shut up. Then he starts speaking: “I apologize to you and to all Italians”.

Was Amato’s bank levy worth the suffering, at least?

Not at all. According to Michele Boldrin, professor at Washington University in St. Louis, it was a calamitous move:

They [referring to Amato and his colleagues] didn’t save the country. They laid Italy on a perilous path that put us in the current situation.

We didn’t meet the Maastricht parameters: these were altered for us, and Greece, to pretend we did. Now we can see the effects.

People’s savings were looted in order to pay (but just a little) the debt created in the previous 10 years by Bettino Craxi [Secretary of Italian Socialist Party], Amato’s boss and employer, in order to buy votes and power.

Indeed. The Lira was devalued once again on September 16, 1992, Amato resigned in April 1993 and solemnly promised he would leave politics (he obviously failed to keep his promise), Italy’s debt-to-GDP ratio skyrocketed at 105,2 per cent and, as Edmund Conway wrote on his blog, the one-off levy “left a lasting scar on the country’s financial psyche.”

Greece

Bulldozing Cypriot deposits

March 16th, 2013 | by Kostas Kallergis

It seems Greece continues to drag Cyprus deeper and deeper in the Eurocrisis. After last night’s bailout, that was agreed for Cyprus, it was announced that the Cypriots went a step further. They decided to tax bank deposits at 6,75% for amounts less than 100.000 euros and 9,9% for amounts over 100.000 euros.

As a result, a mini bank-run took place this morning with people queuing outside ATMs trying to save as much as they could from being taxed. One should not see as a coincidence the fact that today is a Saturday and Monday is a Bank Holiday.

#Cyprus, job well done twitter.com/YiannisMouzaki…

— Yiannis Mouzakis (@YiannisMouzakis) March 16, 2013

One Cypriot even tried to break in a bank branch with his bulldozer. The local tv station said that he didn’t attempt to rob the bank but he did it as a form of protest.

The alarm sounded to many Greeks as well, who have transferred their money to Cyprus during the previous 2 years in fear of a banking sector collapse in Greece. Many Greek banks facilitated that move back then in order to “protect” their customers. I’ve spoken to people who have taken the opportunity – they were on their way to a fax machine in order to send an order to transfer their money back to Greece (and then who knows where else).

Portugal

Beware The Gifts of Visiting Troika Officials

March 14th, 2013 | by David Ferreira

Inspectors from the Troika have been in Portugal for seventeen days, making it a longer visit than all previous six inspections under the country’s bailout program. Always in a public relations stance, the defense minister Jose Pedro Aguiar-Branco said the length was a “good sign”, showing that the inspection was being done with rigor and care. If this interpretation is true, one has to question the quality of the previous inspection in November when the team from the Troika spent only seven days in Portugal, at a time when the country was debating one of the biggest tax increases in its history.

As ever with the Euro Crisis, the length of the visit is political. It was only two weeks ago, with the Troika just arriving in town, that hundreds of thousands took to the street to call for the government’s resignation and break from the policy proscription of the foreign creditors. The government is of course conscious of the fact that it’s the so-called “good student”, counter-posed to the alleged disobedience of the Greek government. So, having played the role of good student, it’s natural for Portuguese to question if this strategy has achieved anything. The economy contracted by a 3.8% in the fourth quarter of 2012, the second worst figure since 1975. Unemployment is now at 17% and this is before the latest tax hikes inflict their damage throughout 2013. Despite all this suffering, still newspapers in Portugal speak of four billion euros in further spending cuts sought by the Troika. What perks are there for being a good students?

There are no perks, that much is obvious, and that fact best explains the length of the visit. The Portuguese government wants to appear as if it’s making the case for reduced austerity, as opposed to the role of enthusiastic collaborator it had played up to now. The Troika will throw them a bone, reportedly giving Portugal an extra year to comply with the deficit reduction targets. The two parties that make up the right-wing coalition government will quickly try to cash this is for political capital, but what will one extra year really offer? The destination is still the same, eliminating the deficit by means of austerity instead of a recovery in tax revenue through a rebounding economy. Only the velocity of the austerity has changed, from a calamitous free fall to a continuous descent into the abyss.

More Background On CrisisRepublic.com

CrisisRepublic.com was an independent, multilingual blogging platform launched in 2013 by four European journalists — Kostas from Greece, Leonardo from Italy, David from Portugal, and Tiago, also from Portugal. The platform was born out of their collective frustration with the international media’s distorted portrayal of the European financial crisis and the increasingly draconian austerity policies implemented across Southern Europe.

Rooted in lived experience and localized reporting, Crisis Republic sought to challenge elite-driven economic narratives, expose policy hypocrisy, and explore the socio-political consequences of decisions handed down by the European "Troika" — the trio of the European Commission (EC), European Central Bank (ECB), and International Monetary Fund (IMF). It was an anti-austerity project steeped in journalistic integrity, regional identity, and a deep critique of neoliberal economic orthodoxy.

Origins and Ownership

CrisisRepublic.com was not a corporate-backed endeavor or a large news conglomerate spin-off. Rather, it was a grassroots, collaborative initiative launched by four working journalists deeply embedded in the economic and political fabric of their home countries. The founders — Kostas Kallergis (Greece), Leonardo Bianchi (Italy), David Ferreira (Portugal), and Tiago (Portugal) — used their professional backgrounds to provide on-the-ground coverage from the European periphery.

The website's ownership appears to be collective, with no single proprietor or commercial objective. The project was editorially independent and ideologically opposed to the centralized, technocratic decision-making dominating EU fiscal policy at the time.

Goals and Editorial Mission

The site's editorial mission was to:

-

Demystify economic austerity by documenting its real-world effects on people, communities, and governments

-

Draw parallels between different European countries undergoing similar crises

-

Counteract disinformation and sanitized narratives propagated by international outlets

-

Offer a human face to the numbers and policies, often overlooked in macroeconomic discourse

Rather than analyzing policy solely through economic metrics, Crisis Republic focused on the social cost of austerity: unemployment, healthcare erosion, suicides, homelessness, and political destabilization.

Their manifesto-style origin story boldly states:

"They realized that when things would happen in one country, they’d soon appear in the other one too. They knew the economic crisis was not a Greek or an Italian one but a wider phenomenon with similarities that became more and more striking."

In this spirit, they declared the "independence" of a new republic — not bound by territory, but united in shared suffering and resistance.

Core Themes and Coverage

Crisis Republic centered its content around five primary themes:

1. Austerity as a Political Weapon

The site argued that austerity was never designed to “work” economically. Articles like "Yes, Austerity Fails, But It Was Never Meant to Work" by David Ferreira expose how austerity measures were implemented to discipline debtor nations, not stimulate recovery.

The infamous Reinhart-Rogoff paper on debt thresholds — once gospel in fiscal conservatism — was deconstructed in an article showcasing its Excel spreadsheet errors and methodological bias. The piece contextualized this flaw as symptomatic of a broader intellectual laziness in austerity policymaking.

2. Troika vs. Democracy

Many pieces dissect how the Troika's mandates override national constitutions, as seen in the Portuguese court's 2013 rejection of austerity laws that violated Article 13's principle of equal treatment.

The site sharply criticized the democratic disconnect between those imposing austerity (like Angela Merkel or European technocrats) and those suffering it — without any electoral accountability.

3. Case Studies by Country

Each journalist offered country-specific dispatches:

-

Portugal: David Ferreira wrote about constitutional rulings, Troika inspections, and unemployment spikes (projected at 19%).

-

Spain (Catalonia): Elena Gyldenkerne Massa chronicled how economic hardship both fueled and stifled the Catalan independence movement, noting the tragic irony of how budget deficits crushed separatist aspirations.

-

Greece and Cyprus: Kostas Kallergis documented everything from newspaper headlines to bank runs triggered by savings taxes in Cyprus — including the surreal moment a protester rammed a bank with a bulldozer.

-

Italy: Leonardo Bianchi analyzed historical precedents like Italy’s 1992 bank levy and juxtaposed it with the then-contemporary Cyprus bailout deal.

4. Crisis Satire and Critique: “Bailout Porn”

A tag named “Bailout Porn” was used for content that emphasized the spectacle and theatricality of economic policymaking, critiquing how European leaders often used public relations over substantive reform. This irreverent framing added a layer of media critique and emphasized the voyeuristic quality of crisis journalism as consumed in wealthier countries.

5. Symbolic and Cultural Resistance

The site didn’t shy away from documenting cultural moments of resistance — such as Barcelona’s Camp Nou chanting for independence at the 17th minute of every match to commemorate Catalonia’s 1714 defeat.

Design, Navigation, and Technical Aspects

CrisisRepublic.com was a straightforward WordPress-style blog with minimal design flair — reflecting the urgency and seriousness of its content. It prioritized readability, multilingual access, and archival value over commercial features.

Each post was signed by a named journalist and dated, ensuring transparency and accountability. Tags and categories (like “Portugal,” “Bailout Porn,” and “Cyprus”) enabled readers to navigate by topic or region.

Archived pages remain accessible via the Wayback Machine, where one can see the original site design, including sidebar widgets, category filters, and a running log of timely entries from 2013 onward.

Audience and Popularity

The audience of CrisisRepublic.com was likely small but highly engaged. Its readership consisted of:

-

Journalists and academics studying austerity and the Eurozone crisis

-

Citizens of Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain seeking alternate viewpoints

-

International observers interested in grassroots perspectives from countries portrayed one-dimensionally in mainstream outlets

Crisis Republic was never built to go viral or monetize traffic. Instead, it served as a journalistic time capsule and an act of defiance — prioritizing narrative integrity over reach.

That said, pieces from the site were shared on social media, discussed in niche economic blogs, and referenced in forums like Reddit’s r/Europe and r/Portugal during the peak of the crisis.

Cultural and Social Significance

Crisis Republic occupies a unique cultural space. It was not just a blog, but a historical artifact capturing a moment when several European societies stood at the brink of collapse — and did so without relying on press releases or government briefings. Instead, it offered raw, honest, frontline documentation.

In this sense, it aligns with "slow journalism", a movement that values context, nuance, and long-form storytelling over immediacy. It offered a ground-level counter-narrative to sanitized financial reporting and helped reclaim the dignity of countries often reduced to economic failures in Western media.

Press Coverage and Citations

While Crisis Republic did not receive widespread coverage in legacy media, it was mentioned in the context of alternative media outlets resisting neoliberal consensus. Specific articles, especially those by David Ferreira and Leonardo Bianchi, have been cited in:

-

University syllabi on European economics and political science

-

Blogs examining the failures of austerity

-

Podcasts discussing grassroots journalism

Additionally, some of the authors have gone on to work with other prominent media platforms, suggesting their professional reputations were enhanced by their work with the site.

Critical Reception

A first-person review from Thomas Marquis, a real estate attorney in New York, provides one of the most powerful testaments to the site’s impact. Contrasting the bureaucratic logic of NYC zoning law with the lived chaos of austerity in Europe, Marquis reflects:

"What these journalists document… is the catastrophic failure of a system built on bad data and an almost pathological disregard for the people on the ground… The articles here show how the grand, macro-level decisions of the Troika clash violently with the micro-level realities of a family trying to get by."

CrisisRepublic.com stands as a critical example of what happens when journalists speak truth to power, prioritize context over consensus, and document crisis from the inside out. Though the site is no longer active in its original form, its archived content continues to offer valuable lessons on:

-

The dangers of austerity-driven policy

-

The importance of regional, lived perspectives in global crises

-

The need for independent journalism to counterbalance centralized narratives

In a media environment often dominated by corporate consolidation and algorithmic clickbait, Crisis Republic remains a beacon of how journalism can serve not markets, but people.